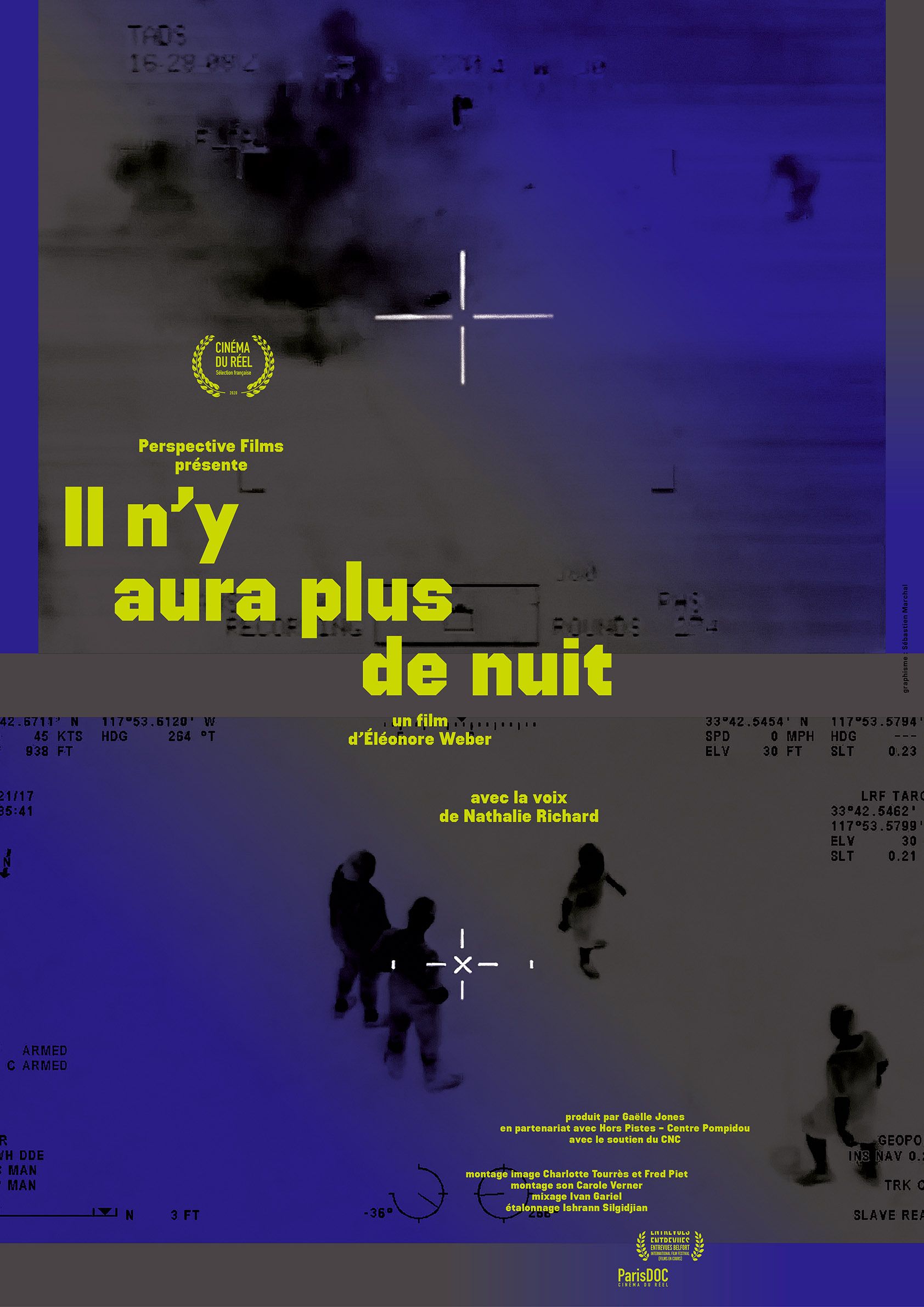

There Will Be No More Night

Synopsis

The ominous title of French cineaste Eléonore Weber’s latest film refers to the fact that the delineation between day and night becomes irrelevant in an age when the world’s most powerful, technologically sophisticated militaries can use long-range infrared cameras to target suspected threats at any hour. Although nocturnal combat and other offensive operations have been a facet of warfare since ancient times, only recently — through advancements in night-vision technologies and weaponry (including unmanned aerial systems or drones) — have pilots and soldiers been able to engage hostile forces from positions of relative safety, and in ways that dehumanize those on the other side of the lens. Consisting almost entirely of point-of-view footage recorded by French and U.S. helicopter gunners’ cameras, mounted on their helmets and capable of detecting the thermal signatures of bodies several kilometers away, There Will Be No More Night provides a chilling look at how the rules of engagement have been bent to favor Western nations whose less-well-equipped “enemies” (in war-torn countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria) must remain on high alert at all times. The latter include innocent civilians or noncombatants who are mistaken as fighters, and whose wrongful deaths — witnessed from the detached vantage of their distant killers — are too often brushed off as an unfortunate consequence of treating war like a video game. Atop these horrifying images, Weber — drawing upon the firsthand experiences of an army pilot named Pierre V. — pours a deeply reflective commentary, spoken offscreen by actress Nathalie Richard. In it she questions the effectiveness and morality of a tactical system that is prone to mistakes (but which generally spares participants like Pierre from suffering legal retribution) and reduces humans to silhouetted shapes on a video monitor. Unlike those grainy images, the world is not black and white, however much its leaders persist in painting complex global issues as conflicts between “evil” and “good,” or between “darkness” and “light.” Such binaristic thinking, Weber suggests, is what allows one side to legitimize its use of unbridled force against the other side, and to falsely claim the high moral ground by virtue of its literally elevated position above people who look like ants. When a photographer can be gunned down because his tripod is mistaken for a grenade launcher, when a farmer is killed because his rake looks like a Kalashnikov, and when soccer-playing kids are held in the crosshairs of a camera-gun as if they were dangers to democracy, one is forced to confront not just the immorality but also the criminality of those and other actions. This hypnotic film concludes that night and its associated comforts (e.g., family time, rest, sleep) will return to those devastated parts of the world only once we achieve that most elusive of goals: when — putting an unlikely spin on its title — there will be no more war.

– David Scott Diffrient

Filmmakers

Eléonore Weber

France

2020

76 minutes

English and French with English subtitles