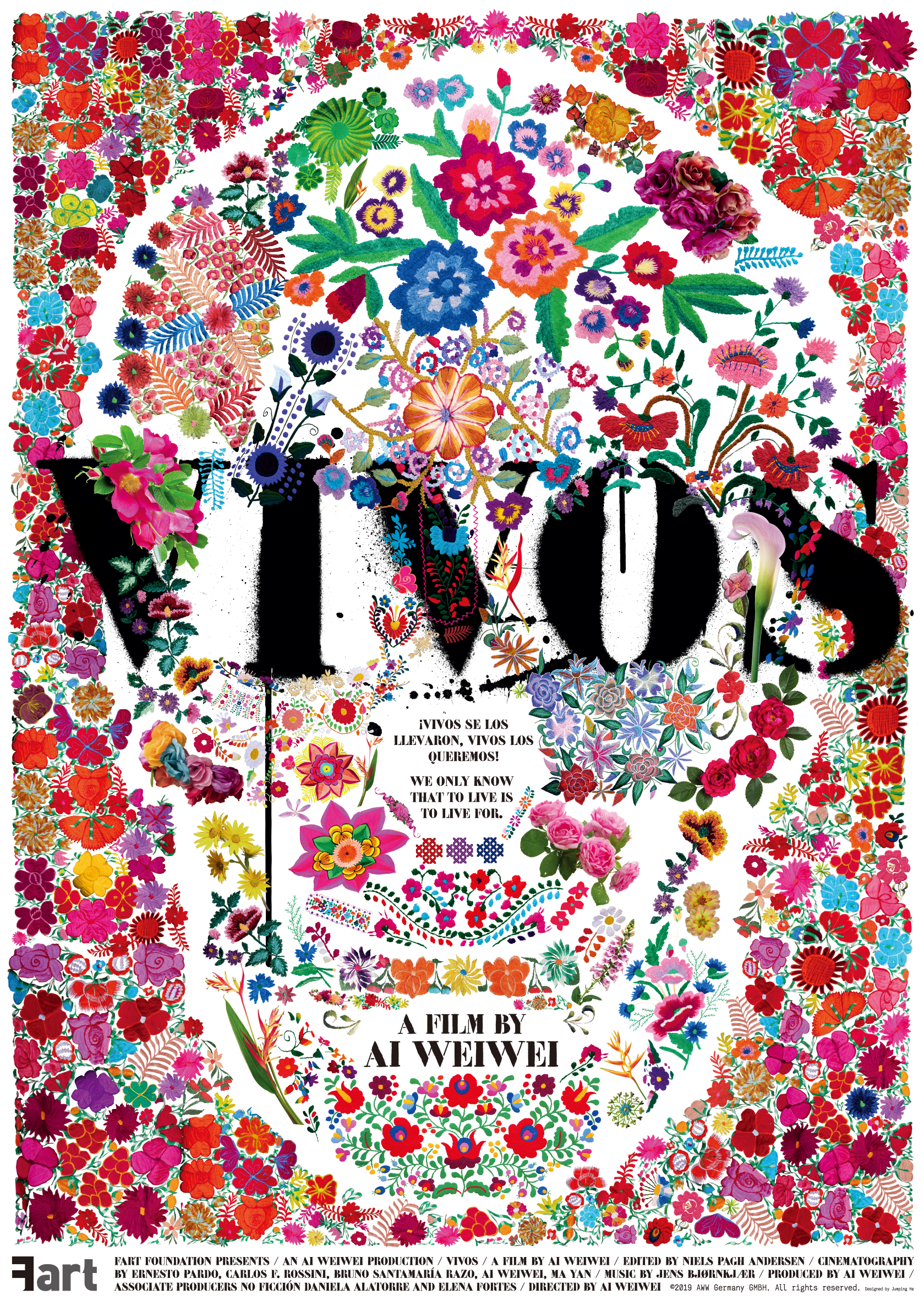

Vivos

Synopsis

Although the exiled political dissident Ai Weiwei initially gained fame throughout the art world for a number of striking photographs and sculptures that take aim at his home country’s government, and while he has a background in making short experimental videos that are viewable in galleries and museums, in recent years the Chinese artist has channeled his creative energy into feature-length documentaries about international human rights issues. From his epic exploration of the global refugee crisis, Human Flow (which premiered at the 2017 Venice Film Festival), to his more intimate but no-less-important look at the collective grief experienced by Mexican villagers following the 2014 Iguala mass kidnapping, Vivos (which premiered at last year’s Sundance Film Festival), Ai has helmed some of the most captivating examples of cinematic rights advocacy of the past half-decade (and, with two more features slated for release over the next few months, shows no signs of slowing down). In addition to providing details about the shocking disappearance of 43 male student-activists, who were abducted by local police and purportedly murdered by members of a drug cartel (though government officials from the Sovereign State of Guerrero are also thought to have been involved), Vivos invites the viewer into the company of those victims’ grieving families. In carefully composed shots that keep the viewer at a respectful distance from its main subjects (who are shown baking tortillas, sweeping floors, and doing other household chores in addition to speaking to the camera), the film offers moments of quiet reflection and artistic restraint. And it does this even as it builds toward a devastating conclusion in which the larger population’s roiling anger gathers force and finally explodes on city streets, in protest scenes that will be familiar to anyone who has participated in pro-democracy marches. At once urgent and deliberately paced, a call to arms and a call to compassion, Vivos puts audiences into a kind of spectatorial limbo. It thus makes the unresolved pain of the dead students’ fathers and mothers — who have yet to receive an honest account of what really happened on that tragic day in September — that much more palpable (despite that distance). If the title of this film seems inaccurate or misleading (given the fates of the missing young men, who are almost certainly dead or permanently disappeared), it nevertheless conveys the idea that the spirit of protest is a living thing, one whose light will not be snuffed out as long as there are people like the residents of Iguala, who, lacking closure, keep the memories of loved ones alive and continue to hold authorities accountable for institutional abuses of power.

-David Scott Diffrient

Filmmakers

Ai Weiwei

Germany and Mexico

2020

112 minutes

English and Spanish with English subtitles